这是一份GLA格拉斯哥大学MATHS1017_1作业代写的成功案例

$2 x+3$ and $x-1$ are factors of $2 x^{4}+a x^{3}-3 x^{2}+b x+3$.

Find $a$ and $b$ and all zeros of the polynomial.

Since $2 x+3$ and $x-1$ are factors,

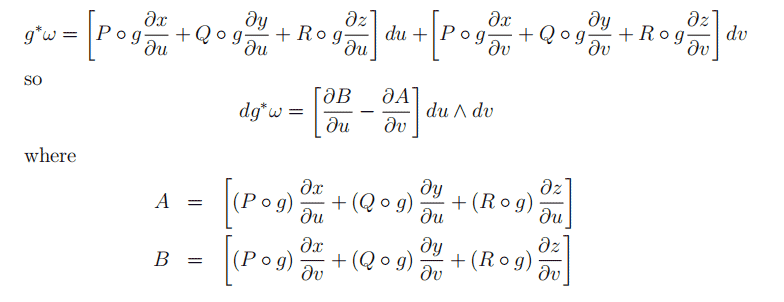

$2 x^{4}+a x^{3}-3 x^{2}+b x+3=(2 x+3)(x-1)($ a quadratic) $=\left(2 x^{2}+x-3\right)\left(x^{2}+c x-1\right)$ for some $c$

Equating coefficients of $x^{2}$ gives: $\quad-3=-2+c-3$

$\therefore c=2$

Equating coefficients of $x^{3}: \quad a=2 c+1=4+1=5$

Equating coefficients of $x$ :

$$

\begin{aligned}

b &=-1-3 c \

\therefore \quad b &=-1-6=-7

\end{aligned}

$$

$\therefore \quad P(x)=(2 x+3)(x-1)\left(x^{2}+2 x-1\right)$ which has zeros of: $\quad-\frac{3}{2}, 1$ and $\frac{-2 \pm \sqrt{4-4(1)(-1)}}{2}=\frac{-2 \pm 2 \sqrt{2}}{2}=-1 \pm \sqrt{2}$

$\therefore$ the zeros are $-\frac{3}{2}, 1$ and $-1 \pm \sqrt{2}$.

MATHS1017_1 COURSE NOTES :

Find $k$ given that $x-2$ is a factor of $x^{3}+k x^{2}-3 x+6$. Hence, fully factorise $x^{3}+k x^{2}-3 x+6$.

Let $P(x)=x^{3}+k x^{2}-3 x+6$

By the Factor theorem, as $x-2$ is a factor then $P(2)=0$

$$

\begin{aligned}

\therefore \quad(2)^{3}+k(2)^{2}-3(2)+6 &=0 \

\therefore 8+4 k &=0 \quad \text { and so } k=-2

\end{aligned}

$$

Now $x^{3}-2 x^{2}-3 x+6=(x-2)\left(x^{2}+a x-3\right)$ for some constant $a$.

Equating coefficients of $x^{2}$ gives: $\quad-2=-2+a \quad$ i.e., $a=0$

Equating coefficients of $x$ gives: $\quad-3=-2 a-3 \quad$ i.e., $\quad a=0$

$$

\begin{aligned}

\therefore x^{3}-2 x^{2}-3 x+6 &=(x-2)\left(x^{2}-3\right) \

&=(x-2)(x+\sqrt{3})(x-\sqrt{3})

\end{aligned}

$$

$$

\therefore P(2)=4 k+8 \quad \text { and since } \quad P(2)=0, \quad k=-2

$$

Now $P(x)=(x-2)\left(x^{2}+[k+2] x+[2 k+1]\right)$

$$

\begin{aligned}

&=(x-2)\left(x^{2}-3\right) \

&=(x-2)(x+\sqrt{3})(x-\sqrt{3})

\end{aligned}

$$