In some sense, the unifying theme of the unit is partial differential equations (we shall see that

although variational principles such as those mentioned in Section 1.1.3 are not differential equations, they are intimately linked to them). You have met several PDEs over the last few years, but

we shall (hopefully) study PDEs in a different manner to how you may have done so up to this

point.

这是一份UCL伦敦大学学院MA30059/MA40059/MA50059 作业代写的成功案

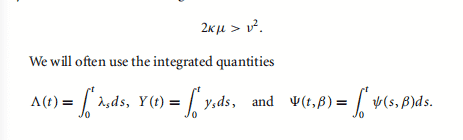

Fix $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{m}$.

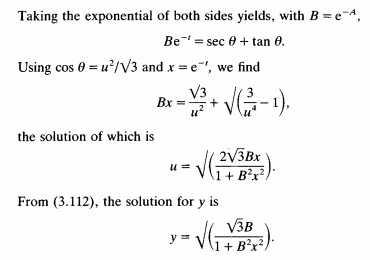

(i) A distribution $T: C_{c}^{\infty}\left(\mathbb{R}^{m}\right) \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$ is called a fundamental solution of Laplace’s equation with respect to the point $\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{m}$ if

$$

\Delta T=\delta_{\mathrm{x}},

$$

that is, equality as distributions. Here $\delta_{\mathbf{x}}$ is the shifted Dirac Delta distribution defined by $\delta_{\mathbf{x}}(\phi)=\phi(\mathbf{x})$ for all $\phi \in C_{c}^{\infty}\left(\mathbb{R}^{m}\right)$.

(ii) Let $\phi \in C_{c}^{\infty}\left(\mathbb{R}^{m}\right)$. As $\phi$ is compactly supported, there exists $\rho>0$ such that $|\mathbf{x}|<\rho$ and $\phi(\mathbf{y})=0$ for all $\mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^{m}$ with $|\mathbf{y}| \geq \rho$. Choose $\Omega:=B(\mathbf{0}, \rho+1)$, so that

$\phi, \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial n}=0 \quad$ on $\partial \Omega$,

and $\mathbf{x} \in \Omega$. Since evidently $\phi \in C^{2}(\bar{\Omega})$, Green’s Integral Representation reduces to

$$

\int_{\mathbb{R}^{m}} N_{\mathbf{x}}(\mathbf{y}) \Delta \phi(\mathbf{y}) \mathrm{d} \mathbf{y}=\phi(\mathbf{x}) .

$$

As $\phi$ was arbitrary, in terms of distributions, this reads

$$

\Delta T_{N_{\mathrm{x}}}=\delta_{\mathrm{x}}

$$

where $T_{N_{\mathbf{x}}}$ is the distribution corresponding to $N_{\mathbf{x}}$, as required.

MA30059/MA40059/MA50059 COURSE NOTES :

We need to find a $v$ satisfying $(1)-(3)$ above. Then we set $G(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}):=N_{\mathbf{x}}(\mathbf{y})+v(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y})$ If $\mathbf{x}=0$, then (3) becomes

$$

v(\mathbf{0}, \mathbf{y})=\frac{1}{4 \pi} \quad \forall y \in \partial \Omega_{0},

$$

so we can just choose

$$

v(\mathbf{0}, \mathbf{y})=\frac{1}{4 \pi} \quad \forall y \in \bar{\Omega}{0}, $$ which satisfies Laplace’s equation in $\Omega$ (and is in $C^{2}(\bar{\Omega})$ ) since it is constant. We now consider the case $\mathbf{x} \neq 0$. In light of the key property of $\mathbf{r}(\mathbf{x})$, namely, $$ |\mathbf{x}| \cdot|\mathbf{y}-\mathbf{r}(\mathbf{x})|=|\mathbf{y}-\mathbf{x}| \quad \forall \mathbf{x} \in \Omega{0} \backslash{\mathbf{0}}, \forall \mathbf{y} \in \partial \Omega_{0},

$$

the requirement (3) becomes

$$

v(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y})=\frac{1}{4 \pi} \frac{1}{|\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{y}|}=\frac{1}{4 \pi} \frac{1}{|\mathbf{x}| \cdot|\mathbf{y}-\mathbf{r}(\mathbf{x})|} \quad \forall \mathbf{y} \in \partial \Omega_{0}

$$

Thus, we let $v$ equal the function on the right hand side of the above for all $\mathbf{y} \in \Omega_{0}$, which is well defined since $\mathbf{r}(\mathbf{x})-\mathbf{y} \neq \mathbf{0}$ for all $\mathbf{y} \in \bar{\Omega}{0}$ and $\mathbf{x} \in \Omega{0} \backslash{\mathbf{0}}$. Furthermore, since

$$

v(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y})=-\frac{1}{|\mathbf{x}|} N_{\mathbf{r}(\mathbf{x})}(\mathbf{y}) \quad \forall \mathbf{y} \in \bar{\Omega}_{0},

$$